In this series, we're highlighting our VERSIONS Alumni. You'll learn about their transformative journeys with…

To serve and protect? The colonial history of police brutality in America

George Floyd’s murder was a tipping point that ignited collective rage around systemic anti-Black racism rampant in the police force. It was an all too well-known reality in Black communities, but the discussions expanded past our community and into the broader public. Protestors took to the streets with their anger, grief, and fear. They ripped off blindfolds that protected both law enforcers and the public from the reality of the Black experience–specifically when dealing with police officers.

I (Liv, Darkspark’s Communication Manager) come from a mixed family–Black and white–with more than a few white police officers. As the conversations about racial tensions between the Black community and police officers took over our TV screens and social media feeds, it also materialized at our dinner table. And how could it not? As a (light-skinned) Black woman with white police officer family members, the conversations about police brutality and the inherent racism were the elephant in the room.

So we talked—a lot. And the conversations we had were incredible: raw, honest, and tear-jerking.

We spent a lot of time discussing the current state of affairs between the Black community and the police force, but as time passed, I realised we didn’t discuss (or understand) the root cause of the issue. There was no doubting the existence of police brutality in our modern-day society, but where did it come from? How did a system meant to protect become Black people’s antagonist?

At a Glance

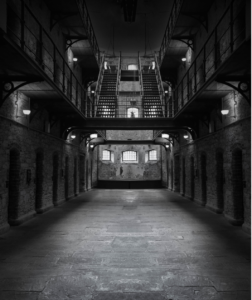

Technically, the first official police department can be traced back to Boston in 1838, but there’s a complex history leading up to their development. The catchphrase to serve and protect is commonly associated with police officers–highlighting their supposed purpose–protecting the communities they serve. But not all communities feel that police really do serve or protect them.

Countless people, specifically Black individuals and communities, fear the police. They hear sirens or see the badge, and panic strikes their hearts while their instincts tell them to run. But conversely, most white communities and individuals are doused in the sense of safety and relief when in the presence of law enforcement. We could even go so far as to say they feel empowered with the belief that law enforcement is on their side.

And there’s a good reason for this discrepancy.

Systemic racism is entwined in policing–it stains the modern-day badge and colours historical events.

But where did this racial tension begin?

Transatlantic Slave Trade

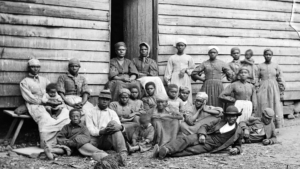

Like many issues centred around race in America, racial disparities concerning policing are rooted in the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade, where, between the 1600s and 1800s, ten to twelve million enslaved Africans were dehumanized and exploited, providing free labour to American plantations and industries. Black people were seen as property rather than human beings. They were given no rights and suffered brutal, if not deadly, consequences when they displeased or disobeyed the plantation owners.

Slave Patrols

It’s no surprise that enslaved people attempted to escape. From horrific working conditions to abuse of all forms, many enslaved people tried to seek freedom. But it was hard to come by. They formed rebellions and attempted to slip out during the night, but the Southern states created a band of people to keep captives captive; these groups are known as slave patrols.

First formed in the Carolina colonies in 1704, their main purpose was to preserve the slavery system. These white men internalized the mission to keep enslaved people in line and ensure that any revolts or escaped slaves were severely punished and returned to their “owners.”

But it wasn’t just out of “civil duty” that these patrols formed. There were laws that empowered them to hunt down escaped enslaved people—specifically, the Fugitive Slave Acts.

The Fugitive Slave Acts were federal laws that explicitly encouraged civilians to recapture enslaved people and return them to their “owners.” The first one was enacted in 1793 but faced heavy resistance. So, instead of disbanding the patrols and freeing enslaved people, lawmakers passed another Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 with even harsher punishments.

The patrollers took on the role of “protecting” their communities from “deranged slaves.” They enforced the law with three main functions:

- Chase down, apprehend, and return runaway slaves to their owners.

- Provide a form of organized terror to deter slave revolts.

- Maintain a form of discipline for slave workers if they violated any plantation rules.

More studies are being done to compare EFT to other treatment methods, but there’s significant proof of its impact.

The Civil War and The 13th Amendment

The Civil War began in 1861, a year after Abraham Lincoln was elected president. He issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which laid the groundwork for the eventual freedom of enslaved people across the country. But, it was limited: it only affected the confederate (Southern) states, was time-consuming to take effect and didn’t grant full rights (such as voting rights). However, its signing initiated the journey to a more progressive nation.

In 1865, slavery was officially abolished thanks to the 13th Amendment–but not everyone was supportive. The Southern states were not aligned with enslaved people being freed and eventually developed Jim Crow laws–laws where Black people became second-class citizens. Additionally, all major institutions and their players supported Black oppression, including churches, medical practitioners, politicians, and the education system.

By this time, the slave patrols had ended–but only by name. Instead, they evolved into militia-style groups that controlled formerly enslaved people and enforced Jim Crow laws. These groups were often formalized as police departments. In fact, we can see residuals of slave patrols not only in the modern structure of police departments but in aspects of their uniform as well. Notably, the telltale star-shaped sheriff badge bears a remarkable resemblance to the slave patrol badge.

North vs South Police Origins

While the Southern states’ police departments had a direct line to slave patrols, the Northern states had a slightly different origin story–but they were both firmly against the “other” and tainted with racism. Many Northern states had community watches that transformed into police departments following Boston’s example in 1838. These former community watches targeted recent European immigrants. But as African-Americans fled the South, Black people became the focus of brutality.

Most white communities weren’t used to being around so many Black people, and as a result of the mass migration, they defaulted to fear and hostility. Stereotypes and biases clouded both the community’s and police’s vision, and they erroneously believed Black people to be inherently dangerous. This resulted in a “protecting whites against Blacks” attitude that these community watches and police departments adopted.

War on Drugs

Fast forward past the Civil Rights movement, which advanced equality nationwide and sought a more progressive society, and pause at Nancy Reagan’s “Just Say No” campaign. This slogan spread far and wide–past the borders of the USA and into other countries, like Canada. Nancy and her husband, Ronald Reagan, took a stand against drug use in America. They formally declared war on drugs–which sounded universally good at the time of introduction.

However, the war on drugs disproportionately attacked Black people. Its discrimination was written in the policies and mandatory minimums of the time; for example, possession of five grams of crack led to an automatic five-year sentence, while it took possessing 500 grams of powder cocaine to trigger the same sentence. At the time, African Americans comprised about 80% of crack users, whereas powdered cocaine was predominant in affluent communities. This resulted in higher incarceration rates for Black people. This was a strategic way to target and imprison them, keeping them as slaves by another name.

The Modern-Day

Today, we see higher incarceration rates for BIPOCs and severe distrust between Black communities and law enforcement across America. The NAACP claims, “32% of the US population is represented by African Americans and Hispanics, compared to 56% of the US incarcerated population being represented by African Americans and Hispanics.” A 2020 study showed Black Americans are 3.23 times more likely than white Americans to be killed by police. With a system literally built to disadvantage Black people and enforced by departments born from the time of slavery–Black Americans are at a severe disadvantage in life.

Today, we see higher incarceration rates for BIPOCs and severe distrust between Black communities and law enforcement across America. The NAACP claims, “32% of the US population is represented by African Americans and Hispanics, compared to 56% of the US incarcerated population being represented by African Americans and Hispanics.” A 2020 study showed Black Americans are 3.23 times more likely than white Americans to be killed by police. With a system literally built to disadvantage Black people and enforced by departments born from the time of slavery–Black Americans are at a severe disadvantage in life.

So, we take to the streets, protesting racial inequities that’s been on hand for centuries. There is a lot of work police departments need to do to help restore trust among the Black community (and BIPOC), but the first step is understanding the historical issues at play. Only then can we try to move forward with open communication and a genuine desire to change.

Family Dynamics

To state the most obvious fact; reality can be uncomfortable. Learning the history of police when I have family members in the service and when so many people rely on them for safety is unsettling.

But discomfort is where real change happens.

At family gatherings, I’ve seen time and time again Black family members retelling their stories of racial profiling and close calls with police officers. They tell these stories with my white police officer family member(s) in the room. And these officers sit and listen. They are forced to face the realities of their discriminatory colleagues and the very real and traumatic impacts of their actions. They engage in conversation about the system, issues, opportunities for improvement, and reconciliation.

I’m well aware this isn’t an opportunity everyone has. But it’s an interesting phenomenon to witness–especially in the time we’re in now. Perhaps the best thing to do is understand the beginnings of racialized systems and discuss it with people operating in the residuals of that brutal history. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s a start.