"Now, I believe in myself. I trust my soul." In this series, we're highlighting our…

A Brief History of Black & Intersectional Feminism

Feminism, often described as a movement for the benefit of all, has unfolded in waves over the years, progressively evolving. At the beginning of the movement, however, it did not include a universal premise and primarily served the interests of upper-class white women. Take, for example, the fact that it took nearly five decades after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, in which (white) women were given the right to vote, before Black women could exercise the same right. Even as Black women suffragists marched for the right to vote alongside white women, they were restricted to the back of women’s marches in the early 20th century after debates around whether they should be excluded entirely.

But even this disparity only recently entered mainstream conversations, despite being highlighted by Black academics and thought leaders for decades. Canadian and American education systems historically glossed over the exclusionary nature of mainstream feminism. Instead, they emphasized its historical focus on the needs and struggles of white women while excluding the plight of Black women. Historically (and in the modern day), the needs of Black women and other women of colour were overlooked as white feminists assumed the role of spokespersons for all women.

Feminist Theory

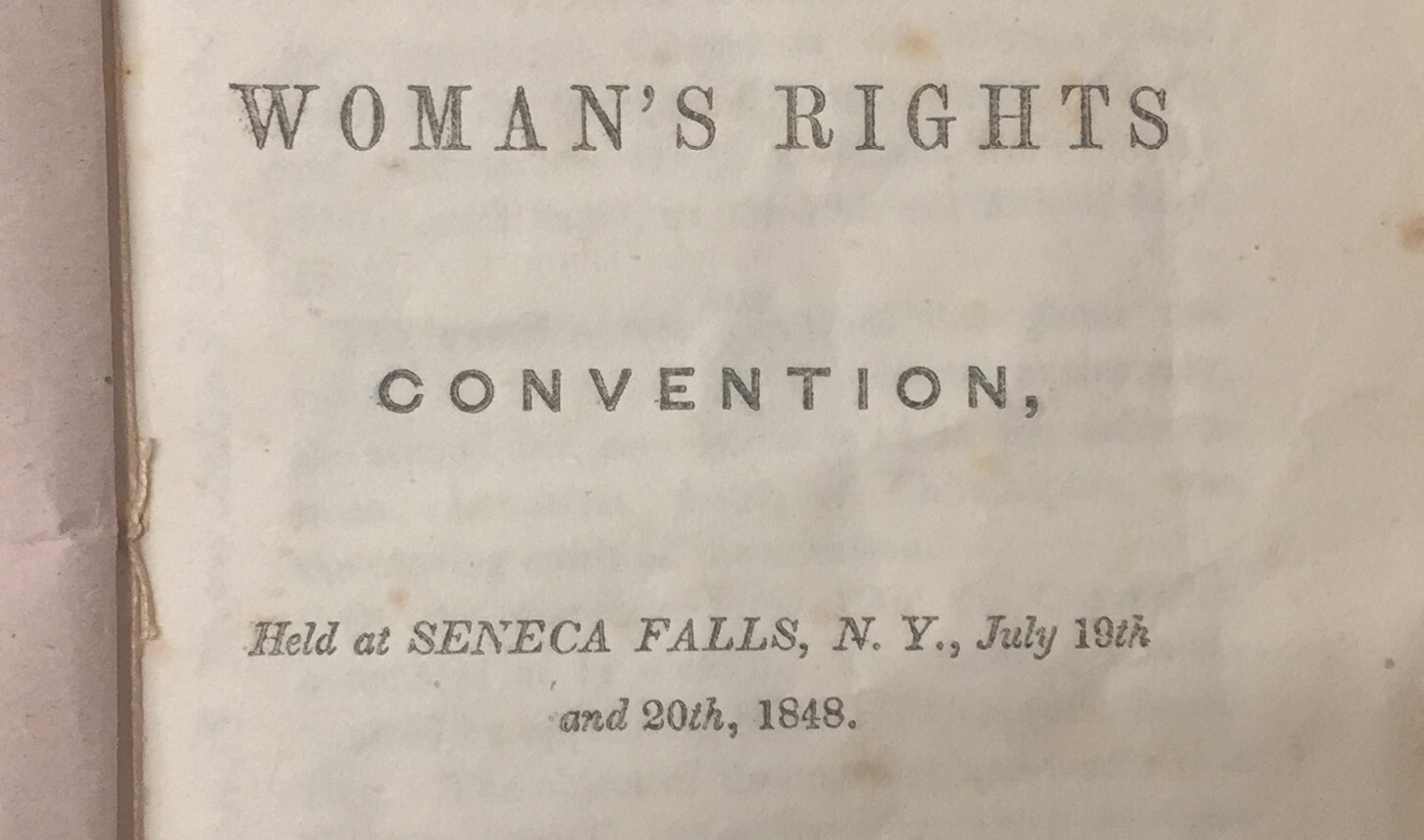

Mainstream feminism, frequently presented as a one-size-fits-all phenomenon on in educational settings and casual conversation,historically centred white women—in fact, that’s why it’s often referred to as white feminism. These roots of mainstream feminism (or “white feminism”), can be traced back to the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention. This gathering is commonly regarded as the “birthplace of American feminism.” However, this historical milestone and the goals of the gathering were primarily focused on the aspirations of white women seeking power over, rather than liberation from, oppressive systems. At this time, the majority of white feminists were more interested in their own liberation, than including African American women in the fight for justice.

Ain’t I a Woman?

Sojourner Truth, who was born into slavery in 1797 and later escaped, emerged as a notable abolitionist and itinerant preacher deeply involved in the anti-slavery movement. By the 1850s, Truth was immersed in the women’s rights movement. Her timeless speech, “Ain’t I a Woman?” delivered in Ohio, pointed out the flaws in gendered assumptions of the time. Truth went head-to-head with the men who claimed women had inherently delicate traits that prevented them from participating in strenuous work and that they needed to prioritize their “female duties.” She pointed out that this “inherent nature” of women they referred to conveniently excluded women of colour. In fact, Black women were seen as unanimously fit for the gruelling and laborious jobs they were forced into for centuries, including slavery and housework.

While Truth was an early public critic of the inconsistencies within feminist discourse, it wasn’t until around 1866 that Black women collectively began vocalizing the necessity for a more inclusive feminism. In “Black Women: Shaping Feminist Theory,” bell hooks makes it clear that Black women did not suddenly become aware of their oppressive state or feminist discourse thanks to the white feminist movement;

“White feminists act as if black women did not know sexist oppression existed until they voiced feminist sentiment. They believe they are providing black women with ‘the’ analysis and ‘the’ program for liberation. They do not understand, cannot even imagine, that black women, as well as other groups of women who live daily in oppressive situations, often acquire an awareness of patriarchal politics from their lived experience, just as they develop strategies of resistance (even though they may not resist on a sustained or organized basis).” (hooks, page 10)

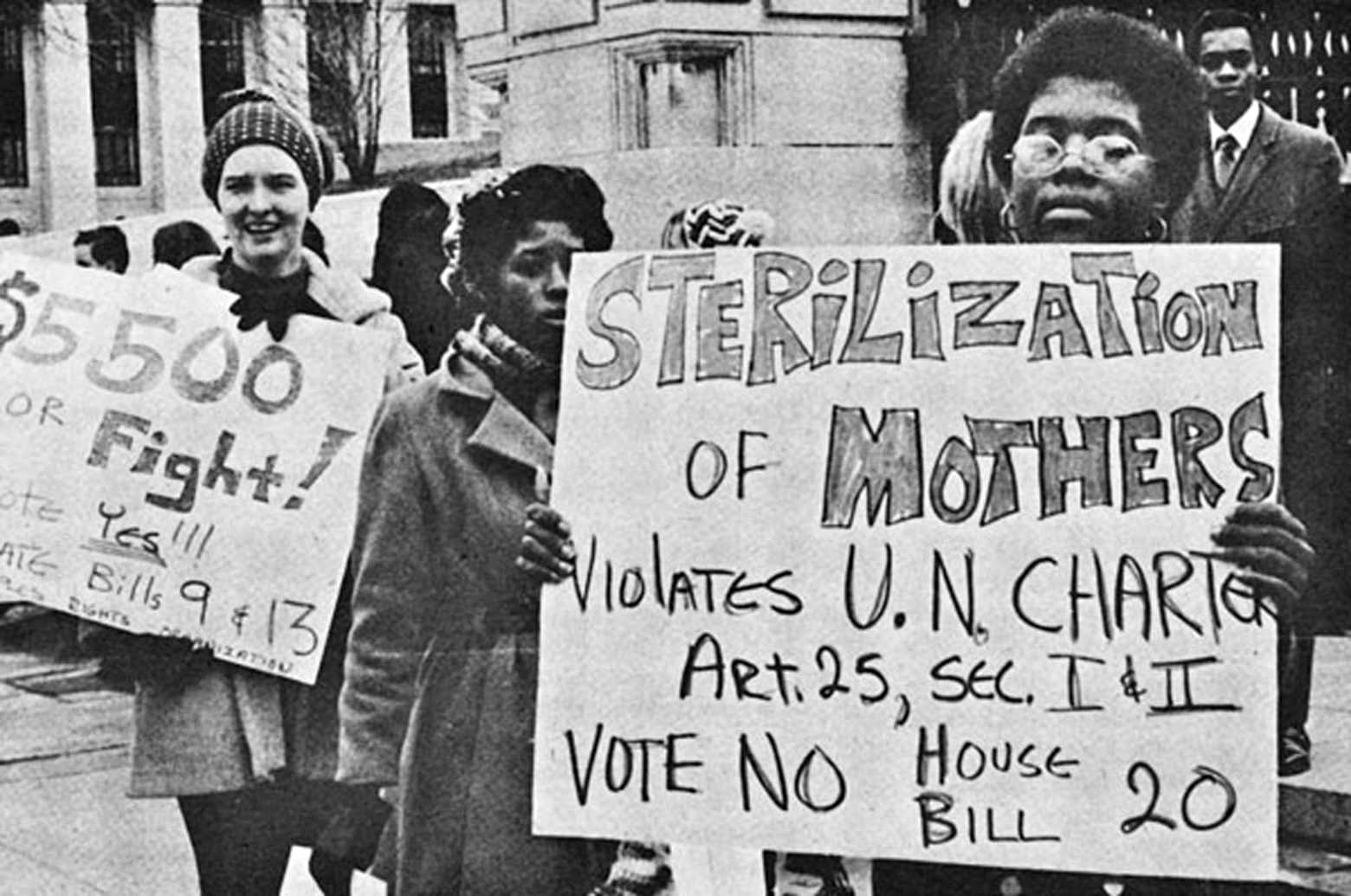

In the 1970s, Black women openly criticized the feminist movement for focusing solely on the issues of middle-class white women. While white feminists continued to push for the right to work outside the home, Black feminists didn’t share this same priority, likely because they had a history of already working outside the “home” as enslaved workers, farmers, and maids. Instead, they advocated for broader societal changes, which became particularly apparent during the era of Roe v. Wade, where Black women fought not just for reproductive rights but also against forced sterilizations.

Forced Sterilizations

Forced sterilizations were written into American law, first in 1907 in Indiana and then adopted by a total of 31 states up until 1978.

Before the 1930s, there was an emphasis on sterilization for racial purity, but this shifted after the 30s to include poor individuals deemed incapable of supporting a family. In 1927, a woman with mental health issues was sterilized after a rape. This sparked the Buck vs. Bell case, where the court argued that “imbecility, epilepsy, and feeblemindedness are hereditary, and that inmates should be prevented from passing these defects to the next generation.” This set a legal precedent allowing states to sterilize inmates of public institutions, furthering the forced sterilization of approximately 60,000 US citizens in more than thirty states, a dark chapter that persisted until the 1970s.

While sterilizations were more common among institutionalized women from the 1930s to the 1940s (as the law permitted), the 60s and 70s saw over seventy percent of sterilizations performed on non-institutionalized women.

Dig a little deeper, and we find that forced sterilization, rooted in eugenics, disproportionately targeted poor Black women and women of colour deemed “unfit” to reproduce. In the southern states, forced sterilization became so pervasive that it was referred to as the “Mississippi appendectomy.” Dorothy Roberts, in “Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty,” documented the horrors of teaching hospitals performing unnecessary hysterectomies on poor Black women for medical practice.

And this persists today. Forced sterilization continues to afflict marginalized communities, with documented cases in Canada of Black and Indigenous women having their tubes tied without consent after childbirth. Moreover, the maternal mortality rate for Black women is 2.6 times higher than that of white women, further highlighting the systemic disparities that persist in healthcare.

Feminism as an Antiracist Movement

Feminism and antiracism movements are inherently interlinked. Thankfully, the need to recognize and acknowledge the distinct struggles faced by BIPOC women was solidified during the third wave of feminism in the late 20th century with the introduction of intersectional feminism.

Coined by Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectional feminism is defined as “a prism for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other.” Crenshaw emphasized that inequality spans across race and gender, highlighting the impossibility of separating the two in the fight against white supremacy and patriarchy.

For centuries, Black women have understood and articulated the exclusionary nature of mainstream feminism but have been pushed to the side. And still, white women are often passed the microphone to speak on behalf of all women—including those of colour. But their experience stands on the shoulders of racism, which often blinds them to the reality of the BIPOC experience. So, as we enter an era of heightened awareness and education, it’s essential that when we discuss feminism, we highlight marginalized voices and acknowledge the diverse experiences and consequences of varying layers of oppression. By incorporating learnings from intersectional feminists on a day-to-day basis, we can all be part of this crucial fight for equity. In the path to inclusion, each little action counts.