"Now, I believe in myself. I trust my soul." In this series, we're highlighting our…

Religious Ferocity in the Black Community

Picture the vibrant scenes of Black churches, where worshippers dress in their finest attire and sit in an atmosphere notably different from other religious settings. Enthusiastic cries of “amen” and other affirmations, coupled with joyful dancing and jumping, make the Black church environment distinctive. But dig a little deeper into Christian history, and you’ll find repeated atrocities committed by white Christians in the name of God against Black people. Yet, in the face of Christian-endorsed historical horrors, Black communities are more devoted to God than others. Why does Christianity serve as a beacon of hope and inspiration for those it has rejected for so long?

The numbers don’t lie

Is the Black community really more religious than others, or is this perception driven by media portrayals and skewed samples? According to the Pew Research Centre’s 2021 report, Black Americans are, in fact, more religious than the American public as a whole. The notable presence of Black churchgoers and gospel followers is not an illusion. Not only are the individuals attending these churches predominately Black but so are the churches they frequent. About 60% of adults who attend religious services say they attend those where“most or all of the other attendees, as well as the senior clergy, are also Black.” It’s fair to say the Black identity is not only strong but important in these settings. But the Black Christian identity wasn’t always so potent or willful.

Is the Black community really more religious than others, or is this perception driven by media portrayals and skewed samples? According to the Pew Research Centre’s 2021 report, Black Americans are, in fact, more religious than the American public as a whole. The notable presence of Black churchgoers and gospel followers is not an illusion. Not only are the individuals attending these churches predominately Black but so are the churches they frequent. About 60% of adults who attend religious services say they attend those where“most or all of the other attendees, as well as the senior clergy, are also Black.” It’s fair to say the Black identity is not only strong but important in these settings. But the Black Christian identity wasn’t always so potent or willful.

Christianity’s pro-slavery stance

Today, the Christian bible is often seen as the book of “good” and “salvation.” In the 1600s-1800s, the Bible was also preached as a path of salvation for all, but it was paradoxically used to justify slavery, with early interpretations explicitly cited as pro-slavery. In some cases, churches even sponsored the journeys of slave ships.

Africans who were forced to America in 1619 and beyond brought with them a variety of spiritual practices, including Islam and traditional African religions and spiritualities. In the early stages of slavery, enslavers didn’t actively attempt to convert the enslaved people under their watch. The mass conversions began when some theologians saw the transportation of enslaved people as an opportunity to spread the Christian message and preached that their souls could be “saved.” Preachers then encouraged enslavers to allow the people they enslaved to attend segregated church services. In these sermons, White preachers would selectively cite passages encouraging enslaved people to obey their masters, further intertwining religion and the institution of slavery.

Literacy and enslaved people

Even with the preachings, one would imagine that Christianity would have had a difficult time being accepted by the people it was forced on. The physical Bible is traditionally important in cementing belief in Christianity. However, enslaved people were denied the right to learn to read, and the Bible wasn’t initially available to them.

In its early stages, Christianity spread in enslaved communities through song. Enslaved people would hear biblical stories and transform them into music we now recognize as “Negro spirituals”— a sort of oral storytelling. This music spread across enslaved communities and helped to infuse Christianity into their belief system and daily life.

Turning the script

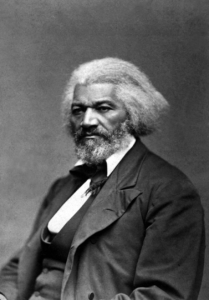

When enslaved people got their hands on the Bible, it was an edited version. Masters and government made sure to omit verses and stories they feared might inspire rebellion. However, the attempts to censor the Bible ultimately failed. Some enslaved people learned to read through untraditional means, and they began to flip the script. For example, Frederick Douglass, a formerly enslaved man turned prominent abolitionist activist, author and public speaker, was taught to read by his master’s wife and eventually taught new interpretations of the Bible, which included messages about equality. He and others realized they had to use the Bible to communicate with their captors. They recognized that enslavers justified the institutionalization of slavery with the Bible, so enslaved people had to prove slavery was not justified by reclaiming the Bible and messages of liberation.

Black Church and the Reclamation

The beauty and innovation of the Black Church is in how it turned a system used to enslave Black people into a tool of unification and perseverance in the face of anguish. Black communities created an entire culture that uplifted and provided hope in an environment designed to crush humanity. They reinvented a religion intended to kill them slowly, and from their own ashes, they learned to grow, develop and adapt with Christianity as their Northern Star.

In fact, the Black Church played a pivotal role in the Civil Rights Movement. Martin Luther King came from a long line of ministers and he himself was a minister of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. He leveraged his position and religion to denounce discrimination. And many churches served to do more than preach religion. They became integral in protests and were often the main organizational ground for activists and leaders to make plans, strategize, and gather.

Of Different Preachings

Despite subscribing to the same overarching religion, modern Black churches tend to preach distinctly different content than white churches. Black churchgoers are often lectured on race relations and criminal justice reform—things that impact Black individuals on a daily basis. White churches tend to focus more on topics such as abortion and sexuality. One Bishop in Charlotte, USA, explains this difference in priority as, “If I’ve never experienced oppression or marginalization outside of the womb, then it’s easy for me to make what happens inside the womb a priority.”

More than prayer

Today, people find more than just faith in churches. Its complex history raises valid concerns, but for church-goers, the Black Church transcends its role as a mere place for prayer. It’s evolved into a holistic community center, extending beyond a physical ground of worship. In Canada, the Church serves as a crucial support system for individuals navigating the challenges of settling into new communities. A survey in 2018 revealed that 63% of Canadian newcomers turned to religious groups for community and networks after their arrival. Newcomers lean on the Church to support them in establishing a community in their new home country.

Across the border, an overwhelming 75% of Black American adults say the Church has had at least “some” role in moving Black communities toward equality. Beyond its spiritual functions, the Church is viewed as a reliable, welcoming place for newcomers to get on their feet and start a new life. It’s seen as a steadfast anchor among storms of change for the people and religion.

Today’s views

The Church and religion, with all their complexities and injustices, present a nuanced landscape. Particularly in Black churches, worshippers harbour a sense of community, purpose, and support despite the historical oppression. In the midst of today’s chaotic world, where the need for connection is heightened, finding refuge in places like the Church can be invaluable for some. As long as these spaces promote unity without causing harm, the Church can be a beacon of hope and motivation. But it’s important we recognize the harmful history and work to ensure a future where religion and Black lives exist to empower one another.